KEVIN DE RUYTER

True-Story Transformation Author

"I have been both the architect and the destructor of my own happiness.

It is humbling to realize that no one else can rescue me from myself.

Healing begins the moment I decide to lay new foundations, even with trembling hands."

— R.M. Drake

Before you scroll any further, I want you to have the full frame of this book. Most readers never see a synopsis at this depth before a release. Treat it as orientation, not a substitute. It lets you see what you are stepping into.

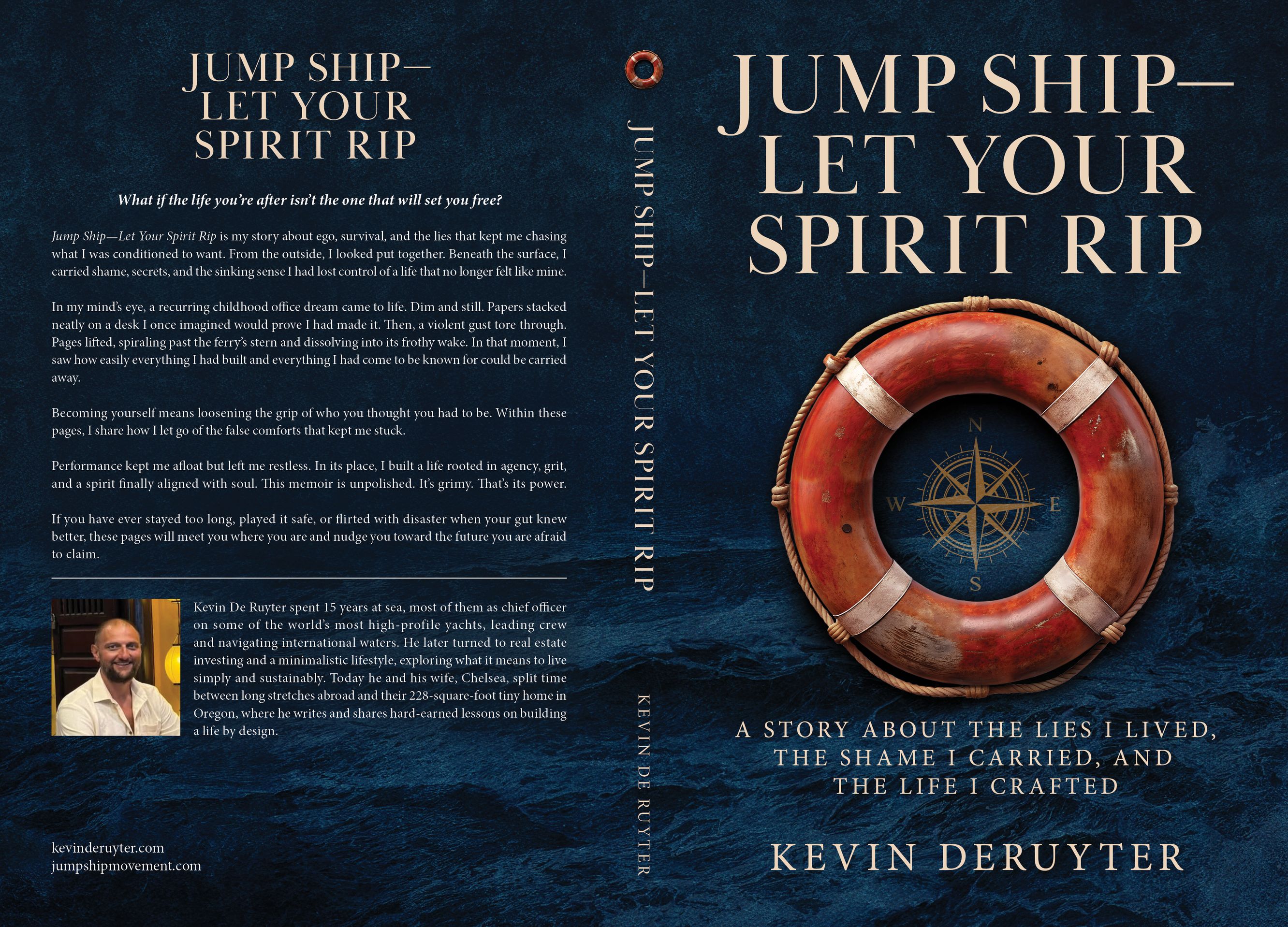

Synopsis for JUMP SHIP—

LET YOUR SPIRIT RIP

This summary of my memoir JUMP SHIP—LET YOUR SPIRIT RIP serves as scaffolding, a frame to walk around before entering the full house. Since you’re reading this, I want you to feel where the floor gives a little and why I chose to build it this way.

This version exists so you don’t have to read every page to grasp the heart of the book. Whether you read it cover to cover or take only the gist, I want you to see the structure of the work: the lies I lived, the shame I carried, and the life I crafted one hard choice at a time.

Recurring childhood dreams of working in an executive suite followed me from the farm to the sea. I imagined a desk piled with paper, a room where I could shut the door and finally feel like a professional. For years I believed that kind of office would prove I had carved out a real place for myself. This book is what I built instead.

A boy learns to keep up, not question.

Before the yachts, before the lies, before I started rebuilding anything, there was the boy who kept pace without complaint. That’s where it starts.

I was the youngest of four in an old farmhouse where the bathroom window iced each winter, and the jeans we wore to the barn stayed permanently stained with cow manure no matter how often we washed them. Our dairy farm sat five miles outside of town. We milked twice a day, every day. My earliest memories aren’t of toys or cartoons but of bottle-feeding calves, hauling buckets through slush, and scraping manure before the bus came.

By the time I could tie my shoes, I had barn clothes of my own. Complaining wasn’t an option. You worked. You kept up. Emotions had no place. Early alarms. Broken gates. Unspoken rules. That was the reality.

My parents were doing the best they could with what they had. They bought the farm in 1980 and worked it every day, through storms, feed costs that outpaced income, and a calendar that never let up. Six weeks after I was born, my mom took a job at the paper mill. My dad stayed on the land. He didn’t explain himself. He didn’t complain. He showed up, kept things running, and didn’t crack. I watched him move through each day like stopping wasn’t an option.

It never crossed my mind to question our way of life. I just absorbed the terms and carried them out.

The rules weren’t posted, but we followed them: help out, stay out of the way, don’t whine, don’t slack. We were farm kids, expected to be useful and tough. I didn’t know how to ask for help because I never saw it modeled. Nobody named what they felt. If you were sick, you still worked. If you were scared, you kept it to yourself.

Love came through effort. Hot meals. Folded laundry. Cows fed before sunrise. The barn thawed by footsteps and breath. That was the language. You either learned it or kept your mouth shut. I wasn’t defiant. I did what was asked.

My boots were always by the door. I got off the bus and walked straight to the barn. No one asked me to. I was chasing a nod, a glance, proof I was doing my part. Not for how I felt, but for what I offered. I thought being good meant I was okay. But good isn’t the same as whole.

I wasn’t acting out. I was fading in. I didn’t speak up. I performed. I adjusted. And I got skilled at it. Too skilled. I could cover discomfort with a chore, a joke, a quick answer. I tracked what others needed so closely I lost sight of what I needed.

By grade school, I noticed how easily I slipped beneath notice. I wasn’t the loudest. I didn’t chase attention. I wanted approval. I learned to blend, to stay out of the way without disappearing. When adults praised me for being helpful and low-maintenance, I leaned in. I didn’t push back. I didn’t say what bothered me. I didn’t point out the ways I felt passed over. I kept those parts to myself.

I came to believe my role was to make things easier for others. If I kept things calm, maybe I wouldn’t get hurt. Inside, I was starting to crack. But it didn’t show as rebellion. It showed as overdoing. I became the one who never made trouble, who stayed agreeable, who outran discomfort with effort.

The shame came on slow. Not from one event, but from a hundred small choices where I stayed silent instead of honest. I gave a version of myself that felt safer. After a while, I started to believe that version was all I had. Shame doesn’t shout. It creeps in and tells you love has to be earned. That being impressive matters more than being real.

I became skilled at pretending. I could look like I had it together and still feel completely alone. But I didn’t know how to name that then. I only knew how to keep moving. So, I did. And I kept that pace for years.

I wasn’t the top student. I had to work harder than most kids to stay afloat. Learning didn’t come easy. I didn’t mind school, but I never felt settled there. I pushed through assignments, did enough to avoid red flags, and made it look like I was fine. I knew how to stay one step ahead of concern.

Sports were one place I felt free. I played varsity football in high school and planned to finish strong. Then I got the chance to work on the maintenance crew at Lambeau Field, so I gave up my senior season. The Packers had been part of my world for as long as I could remember. Getting that job felt like stepping into a dream I used to talk about with my dad.

It was a trade I could live with. I let go of Friday night lights and focused on where the job might lead. I started studying harder, not for the diploma but for the doors college could open. I was sixteen, already inside the gates of the dream I thought would carry me forward.

That dream had a name: a future with the Packers. At the time, I thought it was my dream goal. It felt like it could take me further than playing ever would. The job wasn’t glamorous. It was maintenance. Cleaning. Painting. Fixing. Stocking supplies. Clearing snow. But it came with a field pass.

I could walk the same turf I used to watch from the couch beside my dad. I had traded pads for coveralls, and Lambeau lit up my imagination. The farm was my backdrop, but this place was louder. Brighter. Built for show. It felt like a way out. And now I was part of the machine.

Game days started in the dark and ended long after the stands had cleared. When the players ran onto the field, we kept working. We coiled cables, wiped benches, dragged heaters across the turf. Our radios clicked with updates we had already anticipated. I stayed alert without drawing attention. I learned to act before being asked.

That job showed me what professional work demanded before I had even finished high school. It convinced me this could be the backdoor in. I could work my way up. Study business. Get a sports management degree. Come back to Lambeau one day, not in Carhartts and boots, but in a blazer with an office and a nameplate. That was the plan.

To be part of the Packers and earn a seat at the table. To turn a job into a future. When the acceptance letter from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee came, it felt like movement. I had the work ethic. Lambeau gave me one foot in the door, college the other. Keep going and the rest would follow.

The transition wasn’t clean. I kept my Packers job and commuted back to Green Bay for home games. Monday through Thursday I sat in lecture halls. Weekends split me between Lambeau, the farm, or blackouts in Milwaukee. I still tried to be a good son, a reliable kid. But college ran at a different pace, and I struggled to keep up academically.

I didn’t know how to study. On the farm, asking for help wasn’t off-limits, but work always came first unless there was school or church. I was still afraid to ask for help. I had built a reputation for being capable, and I didn’t want to crack it.

I leaned on charm and effort, trying to stay likable, as if that could make up for what I didn’t know. But that didn’t fly in the classroom. Confusion slipped into avoidance, then into partying. Drinking became the default. Not every night, but enough. Enough to feel free. Enough to numb the pressure. Enough for my future to matter less.

I started skipping class, then covering for it. At first, I brushed it off. Then I started hiding it from my parents. My grades fell. I kept promising myself I’d fix it. Next semester, next time, some future version of me would get it together. But the habits were already setting in.

I carried myself like a good kid on track, as if nothing had changed. But the cracks were widening. After the fall semester, I had planned to spend my winter break on the farm, make some money at the stadium, and course correct. Fate had other plans.

In December 2005, I slipped on the ice walking between house parties. I was drunk. The fracture needed surgery. Winter had locked in. The NFL season wasn’t over, but I was. Off the schedule. Benched. Alone in a recovery that gave me too much time and no idea what to do with it.

More legal trouble followed. I lost my license. With no way to get back to Lambeau and no courage to explain, I turned in my resignation. I told myself it was the right thing. I didn’t want to put the organization at risk or answer questions I wasn’t strong enough to handle honestly. I made the exit easy on everyone else.

I called it temporary. Denial dressed it up that way, but I knew that gate would never open again. I didn’t tell my parents the full story. I still believed I could fix it. That I’d finish school, land a front office job, and reach my dream goal. But the shame kept growing.

I had already turned my back on the path I thought would carry me forward. The wake-up calls came, but I slept through them. Still, I didn’t stop. Not after academic probation. Not after suspension. I kept partying. Kept pretending. I told myself if I could earn a degree, the baggage wouldn’t follow me.

The fantasy was Lambeau—me in a tie, behind a desk—like it could erase everything. But I wasn’t moving forward. I was drifting further from the person I thought I was.

I should’ve gone home. Taken the hit. Regrouped on the farm. Saved money. Sobered up. That would’ve made sense. But home didn’t feel right. Not anymore. Going back to farm full-time scared me. Telling the truth scared me. Different doors, same fear.

When the dream collapsed, the water offered a new direction.

Milwaukee was a mess, but it was mine. I still thought I could clean it up. I had no driver’s license, but I had off-campus housing and classes to attend. Going home after the spring semester made sense. Paying rent for a place I wasn’t living in didn’t. I needed work, fast.

I had lost my grip on my dream goal and I couldn’t drive legally. But I hadn’t lost my survival instincts. A friend told me about a company hiring deckhands on a ferry. I had no experience, but I was curious and desperate. So, I drove to the terminal without a license because I had nothing left to lose.

I walked in like I belonged and filled out the application. That part of me was still alive. The one that could show up, do the work, and get paid. The job cut through the fog. The boat was thundering, fast, and built to move in any weather. It crossed Lake Michigan between Milwaukee and Muskegon, carrying cars, bikes, and passengers on a schedule that never stopped.

No time to dwell. No room for shame. The ferry became a place to rebuild, one shift at a time.

The labor was tough and unforgiving. Even with a fully healed ankle. We tied lines, stacked supplies, scrubbed grease, hosed decks, and cleaned toilets. The company didn’t care about transcripts or excuses. They cared if you worked. And I could work. Farm life had taught me how to sweat through fatigue and earn respect through effort. On the ferry that part of me breathed again.

But it came at a cost. Trying to balance both wrecked the semester. The plan to fix it with finals fell apart. I woke for double shifts, stumbled back into lectures, and nodded my way through the day. I told myself I could juggle it, but really I was trying not to sink; the quick money felt like a lifeline.

On the water I had direction. Back at my flat I was adrift. Summer break came, but I wasn’t free. I ate to cope, drank to disappear, and lied to keep the image alive.

I told my family I was fine and kept talking like I could still land an office at Lambeau. When I stood on the back deck of the ferry and stared out at the lake, I felt oddly calm. The engines throbbed beneath my boots. Wind whipped against my face. The dark chop of the water was different. Out there, I didn’t feel broken. I felt capable.

This job gave me structure again. It proved I still knew how to work, same as I did on the farm. Hands busy. Worth earned. For the first time in years, the motion itself steadied me.

The double life was wearing me down. The harder I worked on the ferry, the worse I did in school. The more I tried to look normal, the more dishonest I had to become. I was too ashamed to go home, too far behind to catch up, and too stubborn to ask for help.

I had to show up for myself in some way, gripping the wheel and obeying every rule, knowing the police wouldn’t notice I had no license unless I got pulled over or wrecked up. I didn’t know it then, but this was the start of a long career at sea. Not yachts, not yet. Just a vessel, a crew, and forward motion.

The ferry gave me what I hadn’t felt in years: direction, momentum, and a way forward that didn’t depend on grades or a polished resume. And even though I was proud of the work I did outside the classroom, I knew it couldn’t walk me back into Lambeau. Not anymore.

By the end of what should have been my senior year, I had veered completely off course. I stopped attending classes. I had no path to graduate. And I still couldn’t bring myself to tell the truth.

In May 2009, I invited my family to Milwaukee to celebrate what they believed was my graduation. We went out for dinner the night before. I let them believe the ceremony was scheduled for the next morning. Then I faked a phone call, claimed the ferry had called me into work, and slipped away before any questions could unravel my deception.

There was no cap, no gown, no name called. I left behind a flat with my confused parents on the couch, my roommates still passed out from the night before, and a lie that let me vanish into an uncharted life.

It wasn’t an isolated choice. It was the lies I lived given form. I thought I could bury my failure under performance, that if I played the role of graduate long enough, the truth would never catch me.

Once I pulled it off, I didn’t have to pretend to be a student anymore. I could start pretending I was a graduate. I didn’t have a degree, but I had a Merchant Mariner Credential. It was a backup plan I had scraped together while everything else had fallen apart.

Alongside it, I had a pile of work uniforms and a handful of practical skills. I knew how to mop a deck, chip rust from iron, tie a cleat hitch, and manage radio traffic without thinking. It wasn’t Lambeau, but it was real. And it was mine.

At the time I thought it was survival, but later I would see it was spirit steering when ego had lost the map.

That fall, I leaned harder into the idea of becoming a mariner full time instead of working one season at a time. I flew to Seattle to visit my brother and took a marine safety and survival course called STCW. It qualified me to work on ocean-going vessels. I didn’t have a clear plan beyond that, but the thought of building a real career had started to take root.

The path back to the Packers was gone. In its place, a kind of wanderlust began to surface. Not dreamy or romantic. Practical, if you can believe it. I needed more than a job. I wanted motion. Distance. Purpose. I was beginning to move in a new direction.

Spirit began steering when ego had lost the map.

Around that time, I started hearing talks about yachting. A few crewmembers on the ferry mentioned it like a rumor you weren’t supposed to take seriously. Better pay. Open water. Foreign ports. At first, I let it roll off me. I didn’t think I had the look or the polish. I didn’t come from that world. But the idea stuck like salt on skin.

A yacht could carry me farther than a car ferry ever would. It offered a way out of the mess I had made. I didn’t know where it would lead, only that I couldn’t ignore it. I had to go see for myself.

At the start of 2010, during the ferry off-season, I drove to Fort Lauderdale. I still didn’t have a degree, but I had enough sea days and certifications to start knocking on yacht doors. I walked the docks looking for work, hoping no one would take a jab at my size or my commercial background.

Most days I left with sunburn, sore legs, and battered pride, knowing I could still outwork almost anyone. I had put on a lot of weight since leaving the farm, but I kept at it. That winter, I landed my first real yacht gig.

The yacht was gone within weeks. A breach below the waterline. An engine room left unchecked. The sea took it fast. We used the collision kit. Tried everything. But in the end, we had to abandon ship. It sank in the Bahamas, deep in the Bermuda Triangle. No lives lost, but the work disappeared along with many of my belongings.

I carried the loss back with me. Frustration. Disbelief. It was the closest I had come to a real break, and the sea had swallowed it whole. But the taste in my mouth for that kind of life remained. It wasn't triumph, but it wasn’t collapse either.

Survival meant finding the next paycheck, the next chance to keep moving. I went back to the ferry for the summer season, already eyeing Fort Lauderdale for winter. That became the pattern: first officer on the ship when the lakes were open, yachts when they weren’t.

Each stretch gave me enough money, enough momentum, to take another step forward. I still hadn’t told my parents the full truth. They believed I was a recent grad figuring out my next move. I didn’t set the record straight. Not yet.

By June 2011, I had logged a few yacht gigs and gained a clearer sense of what it would take to chart a lasting course in the industry, but I had still come up short two winters in a row in my search for full-time work. If I wanted a position on a high-end vessel, I had to carry myself differently.

I couldn’t be the one passed over for seeming too soft or out of place in a world where appearances mattered. I joined a gym and signed a month-to-month lease on a one-bedroom apartment in Milwaukee to live in until fall. It harbored fewer distractions and brought me closer to the kind of freedom I was after.

The progress was slow. I walked more, ate with intention, and minded how I moved through the world. I wasn’t trying to impress anyone. I wanted to be taken seriously. I wanted to feel like I belonged on deck, not like I was sinking inside my own body.

When the ferry season began in 2011, the scale hit 301. That was the line. By the time I made it back to Fort Lauderdale that November, I was fifty pounds lighter and closer to the farm kid I remembered—hauling hay before breakfast, working until dusk without complaint, knowing effort as its own kind of currency.

I left Milwaukee for South Florida as soon as the ferry laid me off, ready to pound the docks. But before I could get moving, the phone rang. Buck had died. A childhood friend, gone. The kind of loss that silences a Packers game when you get the news. We grew up together, and now he was gone before he had a shot at life.

I flew back to Wisconsin, stood shoulder to shoulder with the people who knew him best, and sat through Thanksgiving with an aching heart. The news broke me open, but it didn’t stop me. If anything, it sharpened my need to risk a wider horizon.

Not long after getting back to business in Fort Lauderdale, an email landed from a captain through a crew agency. His yacht had just crossed the Atlantic from Italy. He needed hands. A sliver of an opening, and I was ready to drive a wedge through it.

I spent the next month dayworking on this 130' yacht, showing up early, staying late, doing whatever was thrown at me. Every job felt like a tryout. I didn’t whine. I didn’t flinch. I let the work do the talking.

By Christmas, the other deckhand was gone and the captain pulled me aside. The role was mine. At the start of 2012, I was full-time on Mas Fina. Caribbean winters. Mediterranean summers. Spain. France. Places I’d only ever seen on maps.

It was the kind of job I used to think belonged to someone else. Now I had access to water toys to rip across bays with. Meals I couldn’t pronounce. A cabin to crash in. Steady pay. Insurance. Thirty days paid vacation. Travel perks on top. No more bouncing between ferry docks and daywork scraps. I was in.

On the yacht, no one cared about college. Degrees didn’t matter here. This was yachting, a different world. What counted was if I could scrub a hull clean, tie the lines right, step up when needed, and carry myself in a way that kept me part of the crew.

I was laying down walls on a life I had pieced together, and for once it stood upright. I didn’t talk about the past. I held my head high in the present.

Yachts came with better perks. More world. More unknowns. And me, tested at sea. That winter and summer on Mas Fina felt like moving into a house I’d been building in pieces. Unfinished but finally taking shape.

Survival was turning into motion without a map; on a track I hadn’t plotted but that was already carrying me forward. I still didn’t think I looked the part of a yachtie, but I was in the door now, learning the ropes on the fly. Washing down decks. Scrubbing teak. Detailing jet skis.

I liked being outside, part of a crew, part of a current I didn’t have to steer. There was relief in being just another deckhand, not the failure I left behind. The shame I carried didn’t vanish with salt spray. It stayed quiet, but present.

Yachting moved at a pace that matched me. Months on island time. No rent, no bills, no car. I couldn’t believe this lifestyle existed. I wasn’t burning through savings. I was stacking them. When we had no guests on board, I could disappear in foreign ports, recharge, or wander. Whatever I needed most.

Crossing the Atlantic on Mas Fina was one of those memories that stays etched. We left Fort Lauderdale and set course for Spain. The crossing felt like leaving my old life behind, but the shame crossed with me.

Spirit had been trying to steer all along, but it was here that the direction started to track. That was the start of my Soul Course. I was leaving the Midwest kid who’d flunked out of college and finally embracing a life that wasn’t built by modeling someone else’s blueprint.

Yachting didn’t ask me to be whole. It asked me to perform. To polish the rail, smile for the guests, stay upbeat. I could do all that. I’d been doing it for years. Ego liked the performance. But spiritually, I was adrift. I didn’t admit that for years, not even as the Atlantic rocked me to sleep and the old dream faded behind me.

I was twenty-six when I quit Mas Fina after another winter season in the Caribbean. No plan. No dramatic fall from grace. I just let the long act wind down.

To some, it probably looked like I had made it. I knew better. The career was a hustle of openings and exits. From the outside, it looked like a frame that stood, walls that held. But spiritually, I knew I was living in a house of cards. And it wasn’t a house I wanted to live in.

For my golden birthday, twenty-seven, I booked a family trip to Nashville. I didn’t know it at the time, but that trip marked a return. Not to a place, but to presence. Without the uniform I could be me. I didn’t have to explain or prove anything. Looking back, that was the first hint—I didn’t need to rebuild from scratch. I needed to reclaim who I was.

The months that followed were muted. I picked up contracts when it made sense. I lived out of a bag. I drove my old car. I stopped chasing comfort and started listening for what felt true.

Work didn’t define me anymore. It wasn’t a scoreboard. It was just part of the mix. The real work was internal, making sense of what I had tried to outrun: the grief I hadn’t faced, the stories I still hadn’t told, the parts of myself I had pushed down just to survive.

Eventually I knew I couldn’t keep carrying it unspoken. It needed somewhere to land. That’s when the writing started, not as a hobby or an escape but as the truest work I had ever done.

At first, I wasn’t writing a memoir. I was writing to find out what was still true. I wanted to know if the kid from the farm, the one who looked past the tree line and wondered what else was out there, was still alive beneath all the polish and performance.

I wanted to strip it all back. I didn’t know it would become Jump Ship—Let Your Spirit Rip. I didn’t know anyone else would read it. But page by page, I started coming home to myself. I stopped patching leaks in a sinking hull. I stopped auditioning. I let the shame rise to the surface and looked at it with clear eyes. Not to be consumed by it, but to break the cycle of secrecy that had run my life.

That was when the -ship chapters began to reveal themselves, not as clever titles but as the beams and joints of a house I had been building all along. Each one — stewardship, hardship, fellowship, workmanship, yachtsmanship — was part of the frame. Craftsmanship wasn’t about perfection but instead working with crooked beams and uneven walls until they held.

The life I crafted.

My dad died never knowing I dropped out of college. My crew never knew how close I came to drowning in the identity I wore. Most people only saw the uniform. Underneath it, I was tired of hiding.

The lie I lived was that I had to achieve to belong. The shame I carried was that I had failed before I began. But the life I crafted was built on fear more than freedom. That couldn’t last.

What I reclaimed wasn’t a better job or a bigger boat. It was presence. Aliveness. Breath. I finally understood what it meant to jump ship — not to escape, but to arrive.

Shame once gripped the wheel. Ego held the throttle wide open. Spirit had been waiting, patient and steady. The kid who drifted had found his soul course, and this time he would live it fully.

The farm gave me grit. The sea gave me distance. The reckoning gave me back my name. This book isn’t a trophy. It’s a record of where I fell short, where I turned back, where I stopped neglecting myself.

I wrote it by showing up each day until the story matched the life I was living. I’m not an expert. I’m a man who tried and failed and kept going.

This book is the house I raised from the warped beams of my past.

You now know the arc.

The insights people underline can only be found inside the book.